EKWENSU IS NOT THE SATAN OF CHRISTIANITY: LET’S UNDERSTAND THIS BETTER

Growing up, many of us heard the name Ekwensu and immediately imagined the Christian Devil — a dangerous spirit waiting to destroy people. As children, we were warned never to mention the name. It was associated with fear, darkness, and everything “evil.”

But as I grew older and began to study African spirituality with an open mind, I realised something important:

Ekwensu is not the Satan we were taught to fear.

In fact, the more I learned, the more I discovered how misunderstood this ancient Igbo deity truly is.

So who exactly is Ekwensu?

Ekwensu is a trickster god — a spirit of strategy, trade, war, courage, and negotiation. In old Igbo society, traders called upon him when they needed sharpness in business or guidance in difficult bargaining situations. He represents energy, boldness, unpredictability, and change.

He was also invoked during times of war to strengthen the hearts of warriors at the battlefield. After the war, cleansing rituals were performed before the warriors were fully reintegrated into society — not because Ekwensu was “evil,” but because his intense energy needed to be balanced.

Because of this fierce and restless nature, he was linked to war and victory, especially during moments when communities required bravery or mental sharpness to survive difficult periods.

After conflicts ended, people would “send away” or calm the Ekwensu energy to restore peace. This was not because he was evil — it was because his energy could fuel conflict if left unchecked.

A Balance, Not a Devil

Our ancestors understood balance better than we do today.

Just like day and night, joy and sorrow, calm and chaos — Ekwensu and Chukwu represented different sides of the divine order.

Igbo spirituality never taught that there is a physical Devil roaming around.

Instead, it teaches that the divine forces exist within us, guiding our choices.

When we act with kindness, patience, and love, we express our higher nature.

When we act out of anger, greed, or vengeance, we tap into our lower energy — the Ekwensu side of us.

How Ekwensu Became “The Devil”

When Christianity and colonialism entered Igboland, missionaries needed a “Devil figure” to fit their teachings — but the African spiritual world had no such being.

So deities like Seth (Egypt), Èsù (Yoruba), and Ekwensu (Igbo) — who had qualities such as trickery, chaos, or war — were labelled as Satan.

This interpretation came from Europeans, not from Igbo belief.

Ekwensu never fought God, never fell from heaven, and never tempted Adam and Eve.

These are foreign stories imposed on African cultures.

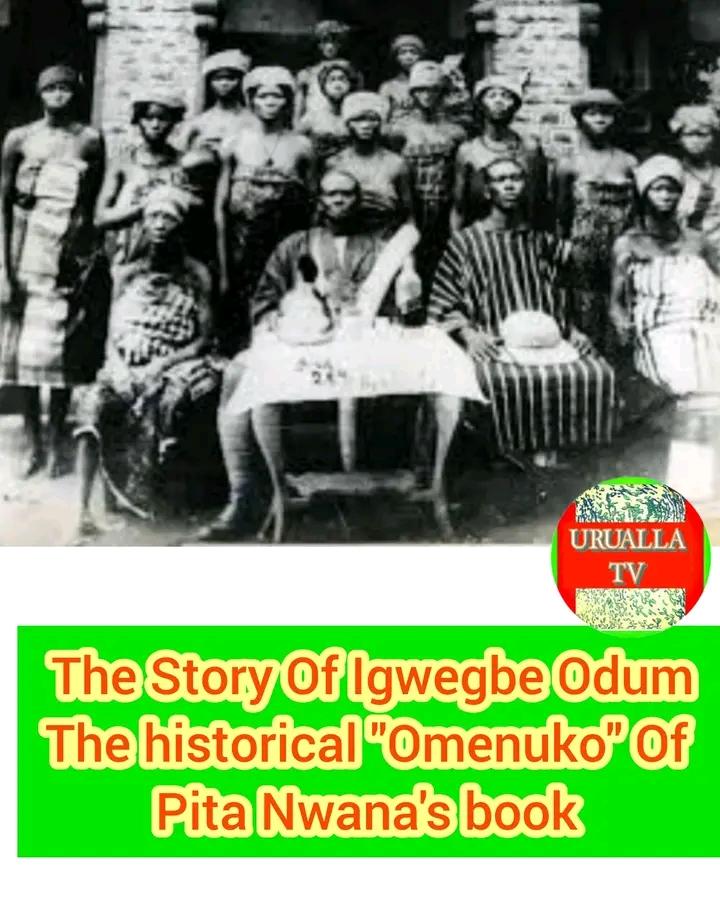

Evidence From Our Communities

If Ekwensu truly meant “Satan,” Igbo people would never name their children or villages after him. Yet we have:

Obiekwensu (Senator Abaribe’s community)

Lekwensu in Umunneochi, Abia State

Umunkwensu in Enugu State

The renowned writer Cyprian Ekwensi

These names show that Ekwensu originally represented something normal and respected — not a demonic figure.

The Real Battle Is Within Us

When someone commits evil, it is not a “Devil” pushing them.

It is a choice — a decision made from the lower part of their spirit.

Igbo spirituality has always taught that when we die, we return to the Ancestors and answer for how we used the divine energies given to us by Chukwu.

This belief existed long before Christianity.

Let’s Reclaim the Truth

Ekwensu is not Satan.

Satan is not Ekwensu.

One belongs to Christian theology; the other belongs to Igbo cosmology.

Our spirituality deserves to be understood on its own terms.

Let us honour our ancestors by learning the truth about our traditions, not the version reshaped by fear and foreign influence.

EKWENSU IS NOT THE SATAN OF CHRISTIANITY: LET’S UNDERSTAND THIS BETTER

Growing up, many of us heard the name Ekwensu and immediately imagined the Christian Devil — a dangerous spirit waiting to destroy people. As children, we were warned never to mention the name. It was associated with fear, darkness, and everything “evil.”

But as I grew older and began to study African spirituality with an open mind, I realised something important:

Ekwensu is not the Satan we were taught to fear.

In fact, the more I learned, the more I discovered how misunderstood this ancient Igbo deity truly is.

So who exactly is Ekwensu?

Ekwensu is a trickster god — a spirit of strategy, trade, war, courage, and negotiation. In old Igbo society, traders called upon him when they needed sharpness in business or guidance in difficult bargaining situations. He represents energy, boldness, unpredictability, and change.

He was also invoked during times of war to strengthen the hearts of warriors at the battlefield. After the war, cleansing rituals were performed before the warriors were fully reintegrated into society — not because Ekwensu was “evil,” but because his intense energy needed to be balanced.

Because of this fierce and restless nature, he was linked to war and victory, especially during moments when communities required bravery or mental sharpness to survive difficult periods.

After conflicts ended, people would “send away” or calm the Ekwensu energy to restore peace. This was not because he was evil — it was because his energy could fuel conflict if left unchecked.

A Balance, Not a Devil

Our ancestors understood balance better than we do today.

Just like day and night, joy and sorrow, calm and chaos — Ekwensu and Chukwu represented different sides of the divine order.

Igbo spirituality never taught that there is a physical Devil roaming around.

Instead, it teaches that the divine forces exist within us, guiding our choices.

When we act with kindness, patience, and love, we express our higher nature.

When we act out of anger, greed, or vengeance, we tap into our lower energy — the Ekwensu side of us.

How Ekwensu Became “The Devil”

When Christianity and colonialism entered Igboland, missionaries needed a “Devil figure” to fit their teachings — but the African spiritual world had no such being.

So deities like Seth (Egypt), Èsù (Yoruba), and Ekwensu (Igbo) — who had qualities such as trickery, chaos, or war — were labelled as Satan.

This interpretation came from Europeans, not from Igbo belief.

Ekwensu never fought God, never fell from heaven, and never tempted Adam and Eve.

These are foreign stories imposed on African cultures.

Evidence From Our Communities

If Ekwensu truly meant “Satan,” Igbo people would never name their children or villages after him. Yet we have:

Obiekwensu (Senator Abaribe’s community)

Lekwensu in Umunneochi, Abia State

Umunkwensu in Enugu State

The renowned writer Cyprian Ekwensi

These names show that Ekwensu originally represented something normal and respected — not a demonic figure.

The Real Battle Is Within Us

When someone commits evil, it is not a “Devil” pushing them.

It is a choice — a decision made from the lower part of their spirit.

Igbo spirituality has always taught that when we die, we return to the Ancestors and answer for how we used the divine energies given to us by Chukwu.

This belief existed long before Christianity.

Let’s Reclaim the Truth

Ekwensu is not Satan.

Satan is not Ekwensu.

One belongs to Christian theology; the other belongs to Igbo cosmology.

Our spirituality deserves to be understood on its own terms.

Let us honour our ancestors by learning the truth about our traditions, not the version reshaped by fear and foreign influence.