THEOPHILUS YAKUBU DANJUMA

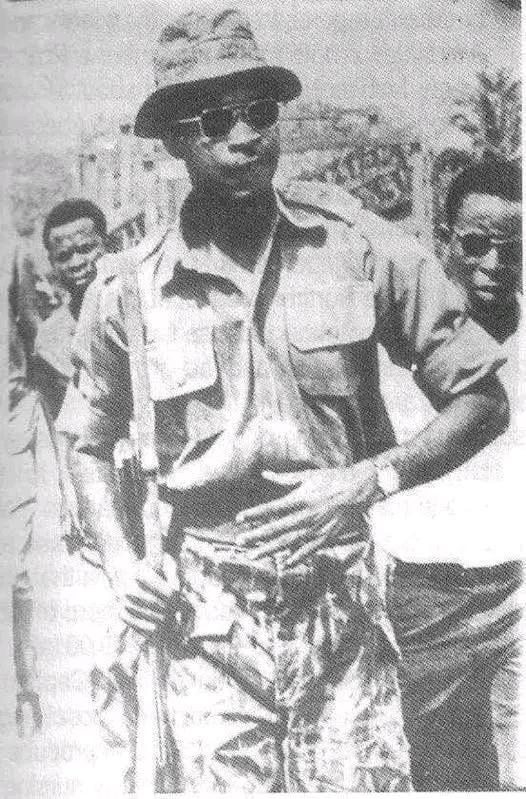

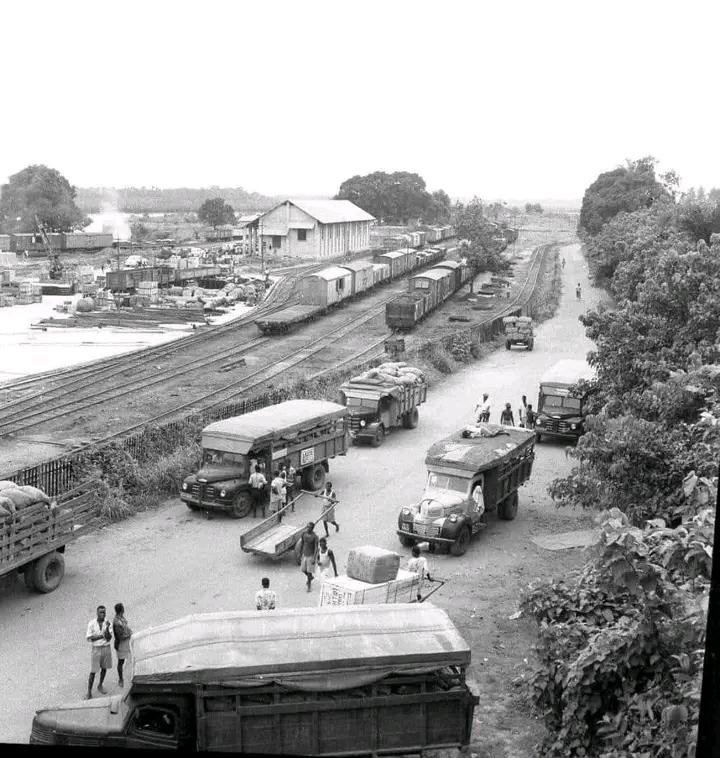

This photograph captures a young Lt. Theophilus Yakubu Danjuma in 1966, a year marked by two vi0lent military upheavals that reshaped Nigeria’s post-independence path. Although often linked to the January c0up, Danjuma was not part of the January 15, 1966 mutiny led by Major Nzeogwu and others. At the time, he served with the 4th Battalion in Ibadan, where he witnessed the political turbulence that followed the coup’s failure and the rise of Major General Johnson Aguiyi-Ironsi.

Danjuma’s decisive and controversial role came later in the July 1966 counter-coup, when northern soldiers revolted against Ironsi’s government. During this operation in Ibadan, Danjuma led the group that arrested General Ironsi and Lt. Colonel Adekunle Fajuyi, an event that ended tragically with their deaths. This moment became one of the defining turning points of the counter-coup and deepened the national crisis.

The image therefore stands as a stark reminder of a young officer operating at the heart of one of Nigeria’s most turbulent years. It reflects the atmosphere of mistrust, ethnic tension, and political fragmentation that engulfed the First Republic and eventually set the stage for the Nigerian Civil W@r

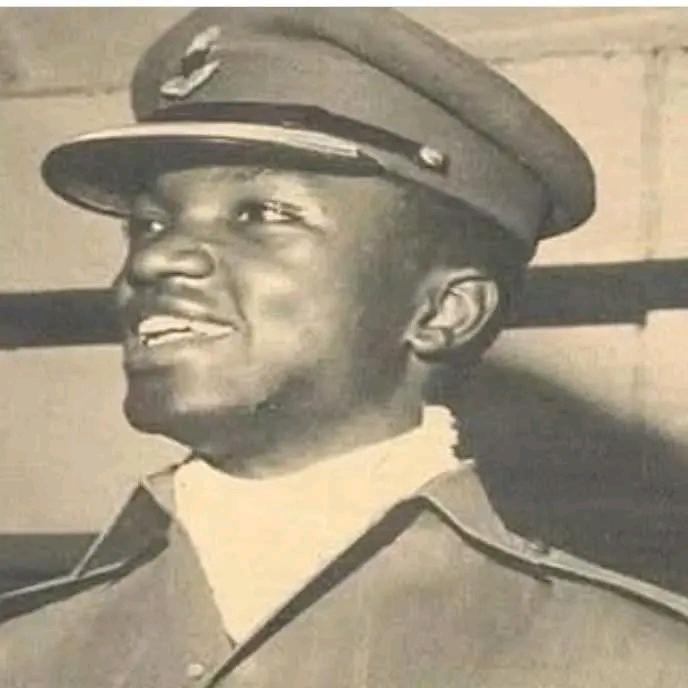

This photograph captures a young Lt. Theophilus Yakubu Danjuma in 1966, a year marked by two vi0lent military upheavals that reshaped Nigeria’s post-independence path. Although often linked to the January c0up, Danjuma was not part of the January 15, 1966 mutiny led by Major Nzeogwu and others. At the time, he served with the 4th Battalion in Ibadan, where he witnessed the political turbulence that followed the coup’s failure and the rise of Major General Johnson Aguiyi-Ironsi.

Danjuma’s decisive and controversial role came later in the July 1966 counter-coup, when northern soldiers revolted against Ironsi’s government. During this operation in Ibadan, Danjuma led the group that arrested General Ironsi and Lt. Colonel Adekunle Fajuyi, an event that ended tragically with their deaths. This moment became one of the defining turning points of the counter-coup and deepened the national crisis.

The image therefore stands as a stark reminder of a young officer operating at the heart of one of Nigeria’s most turbulent years. It reflects the atmosphere of mistrust, ethnic tension, and political fragmentation that engulfed the First Republic and eventually set the stage for the Nigerian Civil W@r

THEOPHILUS YAKUBU DANJUMA

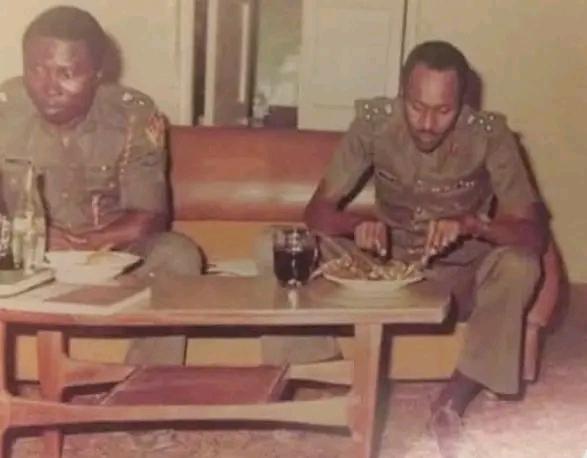

This photograph captures a young Lt. Theophilus Yakubu Danjuma in 1966, a year marked by two vi0lent military upheavals that reshaped Nigeria’s post-independence path. Although often linked to the January c0up, Danjuma was not part of the January 15, 1966 mutiny led by Major Nzeogwu and others. At the time, he served with the 4th Battalion in Ibadan, where he witnessed the political turbulence that followed the coup’s failure and the rise of Major General Johnson Aguiyi-Ironsi.

Danjuma’s decisive and controversial role came later in the July 1966 counter-coup, when northern soldiers revolted against Ironsi’s government. During this operation in Ibadan, Danjuma led the group that arrested General Ironsi and Lt. Colonel Adekunle Fajuyi, an event that ended tragically with their deaths. This moment became one of the defining turning points of the counter-coup and deepened the national crisis.

The image therefore stands as a stark reminder of a young officer operating at the heart of one of Nigeria’s most turbulent years. It reflects the atmosphere of mistrust, ethnic tension, and political fragmentation that engulfed the First Republic and eventually set the stage for the Nigerian Civil W@r

0 التعليقات

·0 المشاركات

·768 مشاهدة

·0 معاينة